- by Kate Prengaman, October 29, 2014 Yakima Herald-Republic

Scientists are searching for the fuels of the future in high-tech laboratories around the world, but last week one research team debuted its new technology at a wood-chipping plant tucked in the forest outside Cle Elum.

That’s because their technology runs on wood chips.

Roasting the wood, which might be otherwise worthless, at high temperatures without oxygen, creates a bio-oil similar to petroleum and a flammable gas that can be captured to run the burners. It also produces bio-char, a charcoal-like material that has applications in agriculture as a soil additive and in water filtration.

The state Department of Natural Resources hosted this demonstration because it’s seeking solutions to Eastern Washington’s biggest forest health problem: dense forests in need of thinning to reduce wildfire and disease risks, which is expensive work.

“When we are talking with landowners about how to improve their forest’s health, (it) involves removing small trees and oftentimes that material doesn’t have much of an economic value,” said Chuck Hersey, a DNR forest health specialist who organized the event with a Utah-based company that developed the technology.

“This technology is one potential pathway for dealing with small, low-grade trees,” Hersey said. “It’s basically turning woody biomass into more dense, renewable energy products that have a higher value than just wood products.”

While the process and its products are still in development, there’s widespread demand for technology to make the forest thinning economically viable. More than 100 people came to see the biomass reactor in action, mostly forest managers, sawmill operators and renewable energy researchers from around the state, Hersey said.

The biomass reactor, which harnesses a process known as fast pyrolysis, was developed by Amaron Energy, based in Salt Lake City. Eric Eddings, co-founder and professor of chemical engineering at the University of Utah, gave tours of his system.

Built in a 45-foot-long freight container, it’s a self-supporting mobile unit. Inside, heat radiates off a large kiln that looks like a big propane tank. Inside is a chamber that spins to rotate the wood chips so the burners on the outside can heat them evenly.

It’s capable of processing 20 tons of wood chips a day, Eddings said. The design is a scaled-up version of a half-ton-per-day prototype Amaron Energy built and tested last year, he said. There’s a control station inside, so operators can adjust and monitor the process. During the tour, the kiln was running at 550 degrees.

“What we are really attempting to do is take the wood molecules themselves and trying to break them up to produce a gas, a liquid and a solid char,” Eddings said. “If you think of your charcoal barbecue, those briquettes, that’s wood that’s been pyrolysized like we are doing here, but compressed into briquettes.”

You have to add lighter fluid to your charcoal to get your grill burning because the pyrolysis process that made the charcoal separates the flammable liquids and gases from the charred wood, Eddings said. In Amaron Energy’s system, those gases and liquids are captured for beneficial use, he said.

“That’s why we do it in the absence of oxygen. We don’t want to burn that off; we want to collect it and capture it and condense it into a liquid form,” Eddings said.

Eventually, he thinks the captured gases will be able to provide most of the power to run the reactor, but for the demonstration, the gas was burnt off in a flare while a propane tank powered the process.

The liquid oil is collected in big plastic tanks. It’s similar to crude oil, but it’s not an exact match for petroleum, so it can’t be sent straight to an oil refinery. There are chemical techniques to treat the oil so that it can be refined, but that raises the costs, Eddings said.

Instead, researchers are developing other ways to refine and use the bio-oil, said Manuel Garcia-Pérez, a Washington State University professor who studies biomass energy. It could be used instead of oil to make plastics, for example, he said.

The char already has a market, Garcia-Pérez said. It can be turned into activated carbon that is used for wastewater treatment or water filtration, or it can be added to soils to increase their productivity.

“It’s very porous, like a sponge, so it will absorb moisture and nutrients and helps retain water and nutrients in shallow soil,” Eddings said.

The char looks like fine wood chips, turned black. That’s exactly what it is, but for the process to run smoothly, it requires finely chipped and sorted wood.

The wood chips used at the demo came from a thinning treatment designed to reduce fire risk at the nearby Suncadia development, said Jim Dooley of Auburn-based Forest Concepts. His company creates the equipment needed to turn waste wood into the perfect chips for use in energy technologies like Amaron’s.

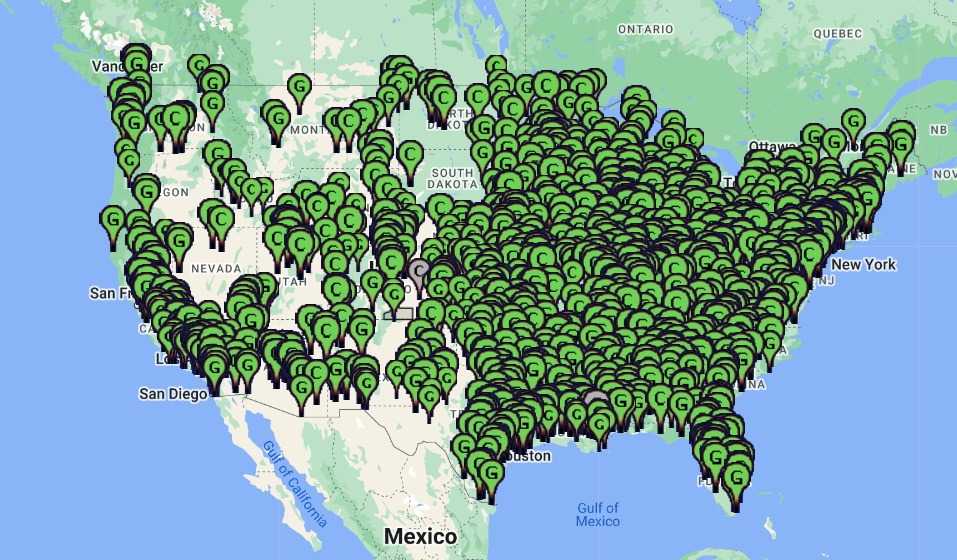

Amaron is far from the only company looking to turn waste wood into useful energy. There’s discussion of a burning wood chips to heat and power Central Washington University, and in 2012, the U.S. Department of Agriculture gave Washington State University and the University of Washington $40 million each for research on the development of sustainable wood energy industries.

A major challenge facing all the technologies in development is that the wood sources are often in remote regions, far from sawmills or paper plants, Hersey said. Hauling the wood is expensive, so that makes it hard for wood energy to compete against cheap natural gas and hydropower.

One advantage with Amaron’s technology is that the mobile units could be operated in remote areas where the forests are being thinned, Hersey said. Then, only the higher value end products need to be transported away, he said.

It sounds good, but Eddings said there’s still plenty of bugs to work out before his technology will be ready to be produced for commercial use, and he’s not sure how much a mass-produced version would cost. He decline to say how much Amaron Energy had invested in developing the technology so far, but the project received a $187,500 grant from the Utah Department of Transportation in addition to private funding.

This commercial scale unit, which can be operated by two people, was just finished in September and the Cle Elum demonstration was just its second test run.