Few in our nation’s capitol city think twice when they throw stuff “away” — nor do they think about who lives where “away” is. Fitting a national trend of environmental racism, it should be no surprise that DC’s waste has long impacted communities of color in one of the most segregated metropolitan areas in the country. (Black-white racial segregation in the Washington, DC area is considered “extreme” and is 17th worst in the nation.)

Before waste actually goes for disposal, much goes to a transfer station first. Transfer stations exist to move waste from small collection trucks into big trucks for longer-distance hauling. In 2000, the EPA’s National Environmental Justice Advisory Council noted that waste transfer stations “are disproportionately clustered in low-income communities and communities of color.”

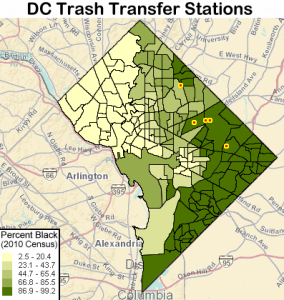

DC’s Department of Public Works (DPW) runs two large transfer stations, in black communities at Fort Totten and Benning Road. These transfer stations are large enough to take care of the city’s needs, but a proliferation of private transfer stations cropped up years ago, in the absence of regulations. Of about 15 that opened, many have since been closed (after much struggle), and some are still being demolished, yet three remain — all clustered in Ward 5, in the adjacent black residential neighborhoods of Brentwood and Langdon. Residents of these neighborhoods have been struggling to close these private transfer stations for three decades. They spoke passionately about their experiences at a Feb 5th, 2014 DC City Council hearing where Ward 5 Councilman McDuffie was joined by other members of council in pushing a bill to increase enforcement on these facilities. In addition to nuisances like odors, “vectors” (seagulls, rats), and trucks (and their diesel exhaust), transfer stations are also a source of airborne mercury pollution from sources such as broken fluorescent bulbs.

1:37 – Mike Ewall, Energy Justice Network

1:43 – Michelle Bundy, Brentwood Community Association

1:49 – Hana Heineken – DC Sierra Club

2:25 – Martha Kinter Ward – Southcentral Community Association

2:40 – Reverend Morris Shearin, Israel Baptist Church

3:48 – Councilman McDuffie

Of the waste collected at the city’s transfer stations, the one facility that gets the largest share of DC’s trash is the nation’s fourth largest incinerator, in Lorton, Virginia. The rest is split among a few southeastern Virginia landfills, far from population centers. We know that the trash incinerator industry in the U.S. is disproportionately located in low-income communities and communities of color.

Some argue that it’s not discrimination if it’s not intentional, or if a people of color moved to where the polluting industry was first. Academics have argued back that this “chicken or egg” debate is beside the point, as what matters is the community impact, not the intent. Intentional discrimination is hard to prove. Even though the courts no longer allow private lawsuits for Civil Rights Act violations unless you can show intent, it’s still considered a violation of the Civil Rights Act when agencies (like the state agencies that grant pollution permits to incinerators) permit facilities in locations where doing so creates a discriminatory effect. [See my environmental justice law journal article for background on this.]

Lorton, VA is an interesting case of environmental racism as it represents both the chicken and the egg. Lorton was home to DC’s prisons from 1910 until 2001. The youth prison, added to the complex in 1960, is adjacent to the county’s landfill that was located there in 1973. In the early 1980s, another landfill, a private one for construction and demolition waste, opened on the other side of the prison. Just a few years after the youth prison opened, a group of over 50 black Muslim youth inmates rioted, set fires, broke windows and damaged the chapel. In 1985, methane migrating from the county’s landfill entered the plumbing system, causing blasts that killed one inmate and critically burned another, forcing the prison to be quickly evacuated. Inmates were returned after several months, once gas vents were installed. Even when not at explosive levels, exposure to the toxins in landfill gas has been found to cause 4-fold increases in bladder cancer and leukemia incidence in women.

Siting major industrial polluters next to prisons is a stark form of environmental racism, as the victims are physically trapped next to the pollution source at all times, not just financially trapped in neighborhoods where spending some time away from the polluters may be possible. In response to comments by this author on a coal-to-oil refinery proposed adjacent to a state prison in Pennsylvania, the U.S. Department of Energy admitted, perhaps for the first time, that a minority inmate prison population constitutes an “environmental justice” community that could be disproportionately impacted in violation of the Civil Rights Act. Unfortunately, the agency concluded (incorrectly) that there would be no violation of civil rights because the refinery would be staying within the pollution levels allowed by their state permits.

I-95 Energy/Resource Recovery Facility (Covanta Fairfax trash incinerator) in Lorton, VA. [See us in 2013 CBN TV news]

In 1990, the fourth largest trash incinerator started up, adjacent to the landfill and youth prison, capable of burning 3,000 tons of trash per day. Owned and operated by Covanta, the nation’s largest incinerator corporation, the incinerator burns a lot of DC’s waste and the resulting toxic ash is dumped in the county-owned I-95 Landfill next door, which closed in 1995 to all but incinerator ash.

Incinerators are the most expensive and polluting way to manage waste or to make energy. They’re far more polluting than coal power plants and are worse than landfills. They turn trash into toxic air pollution and toxic ash, making for smaller (but more toxic) landfills.

To make the same amount of energy as a coal power plant, trash incinerators release 28 times as much dioxin than coal, 2.5 times as much carbon dioxide (CO2), twice as much carbon monoxide, 3.2 times as much nitrogen oxides (NOx), 6-14 times as much mercury, nearly six times as much lead and 20% more sulfur dioxides.

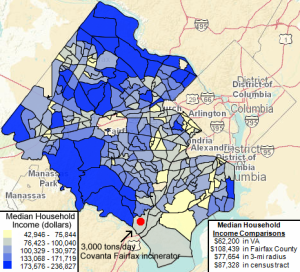

The “chicken or egg” situation flipped when the prisons were closed in 2001 and a large new housing development was built, right up against the incinerator and landfill. The development was populated between 2002 and 2006 with a very diverse community, mainly people of color. The closest neighborhood is 26% white, 32% Asian, 31% black, 8% Hispanic, and 5% multi-racial/other. It’s now considered to be the 12th most diverse community in the nation. The further you get from the waste facilities, the average income and percentage of white people increases.

The issue of race vs. class is an interesting one here. We know from studies like Toxic Waste and Race in the United States that race is more of a defining issue when it comes to where hazardous waste facilities are located. For example, if you had a theoretical low-income white community, and a middle-income community of color, and asked which community is more likely to have a hazardous waste facility try to locate there, it would be the middle-income community of color more often than not. In Lorton, you see something similar. Lorton is in Fairfax County, Virginia — the 3rd wealthiest county in the nation. The median household income in the closest neighborhood is just over $87,000, higher than the state or national averages. However, in the context of affluent Fairfax County, the neighborhood is relatively lower-income.

In the neighborhood closest to the waste facilities, there are walls around the borders of the development. The view over the south wall is of a giant hill (Lorton Landfill) lined with evergreen trees that appear small compared to the mountain of waste. The view to the west is of a tall smokestack, towered over the community. Some of the closest residents, living on the other side of the wall, can hear the constant back-up beepers of the trucks, but had no idea it was an incinerator, thinking it was just construction noise that may go away some time, not the endless sounds of a giant trash-burner being fed.

How did this happen? Was it a form of redlining, where people of color are steered into communities neighboring giant waste facilities? Why were residents not informed of these dangers before moving in? Was it just innocent “market-efficiency” that caused the not-quite-as-affluent people of color to buy here, rather than in the wealthier, whiter parts of the county? No matter how it came to pass, the impact is still unequal, and the health consequences of living next to incinerators and landfills will be felt more by people of color than the white residents of the region.

DC’s contract with Covanta expires at the end of 2015. Under the mayor’s Sustainable DC plan, the city has a goal of zero waste by 2032. However, this goal is often framed in the plan as “zero waste to landfill,” which is code language for “burn it and pretend that the toxic ash doesn’t go to a landfill.” The “zero waste to landfill” idea is not true zero waste, and incineration has no place in a zero waste plan. However, using $300,000 in DC tax money allocated for Sustainable DC, the city is paying an incinerator-friendly consultant with little zero waste experience to come up with a study of the options. The study is rigged in favor of incineration technologies, even though city officials now know that proposing to build a new incinerator is politically and economically non-viable.

The study is going to look at options to build a new waste disposal facility in the district (which would have to be an incinerator of some sort, since there is no space for a landfill) or to partner with Maryland or Virginia counties on building a regional facility. DC’s Department of Public Works has looked into the possibilities of building an incinerator in DC to serve both DC and Prince George’s County, MD — as well as the possibility of partnering with the proposed trash, sewage sludge and tire incinerator planned for Frederick County, MD. The Frederick County proposal has been fought by area residents ever since it was proposed about eight years ago. Even though that incinerator was finally just granted its pollution permits by the state, the project is financially at risk because Carroll County, the other county partnered with the project, sees it as a major financial risk and has set aside $3 million to pay to get out of the contract. For DC or any jurisdiction to step into their place would be economic foolishness.

While the city would be crazy to even try, it’s been fairly clear that if there is any attempt to build a new incinerator in DC, the most likely place it would go is Benning Road, where the city has the space and infrastructure already. The Benning Road community has already been burdened by pollution: the city’s old incinerator operated there from 1972 to 1994; the oil-burning Benning Road Power Plant operated there from 1968 to 2012, leaving behind a toxic contaminated site; an old leaking Kenilworth Landfill (now a Superfund toxic waste site) is next door, and the city operates one of their two major waste transfer stations there.

Residents in DC, in the Maryland Counties of Prince George’s, Frederick and Carroll, and in Fairfax County, VA are all rising up to stop the environmental injustices posed by these industries, and are striving for real zero waste planning, as other forward-thinking communities have been pursuing. Please get in touch and join us!