- by Kevin Simpson, August 31, 2014, The Denver Post

From the living room chair where he sat reading around half past 9 on a May evening, Ron Baker heard the boom and felt his century-old Greeley farmhouse shudder, sending a menagerie of plastic horses toppling from a bedroom shelf.

He stepped out the back door and aimed a flashlight at the thick, ancient cottonwood that leans over the roof, expecting to reveal a snapped limb as the culprit. But he circled the house and found nothing amiss.

About a half-mile down the county road, Judy Dunn had been sitting in bed watching TV when she felt her brick ranch house shake and heard the windows rattle, making her wonder if an oil or gas well had blown.

A few miles away in the city, Gail Jackson joined neighbors spilling out into the street, wondering if a plane crash had triggered the big bang and sudden vibration that dissipated as quickly as it arrived.

All over, phones rang and neighbors compared notes as the mystery unraveled: Weld County had felt the tremors of a magnitude‑3.2 earthquake — jarring but accompanied by little, if any, damage.

In an area peppered with wells pulling energy resources from below ground — and many pumping wastewater from the process back into it through injection wells — an old question resurfaced: Could the same geological tinkering that has revved a formidable economic engine also trigger potentially damaging earthquakes?

“I knew there had been speculation around injection wells causing seismic activity,” Baker says. “This sort of confirmed what I’d been reading.”

Speculation has turned to full-on investigation as researchers from the University of Colorado jumped at the chance to gather data — and within days had set up a network of seismometers surrounding the estimated epicenter.

State regulators eventually zeroed in on one high-volume injection well and had its operator shut off the flow for 3½ weeks before resuming activity on a gradual basis, while the CU scientists track seismic activity nearby.

The unexpected opportunity revives the concept of “induced seismicity” explored in Denver more than half a century ago at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal chemical weapons plant and then in oil and gas fields of western Colorado into the 1970s.

The Bureau of Reclamation has tracked induced seismicity since the 1990s in a river desalination project in the Paradox Valley, but the issue largely slipped under the radar until the industry boom of the past several years.

The Greeley quake, in a region not known for extensive seismic activity, came on the heels of research out of Oklahoma, a state also undergoing intensive oil and gas extraction and wastewater injection. That study linked a stunning spike in earthquake activity to the pressurized fluids pumped far underground — where, scientists say, they migrated to and essentially lubricated existing faults.

But while interest has ramped up in Colorado and elsewhere, the issue remains far from settled. The wells, long regarded as an environmentally responsible way to dispose of wastewater, have pierced the landscape for years, mostly without seismic drama.

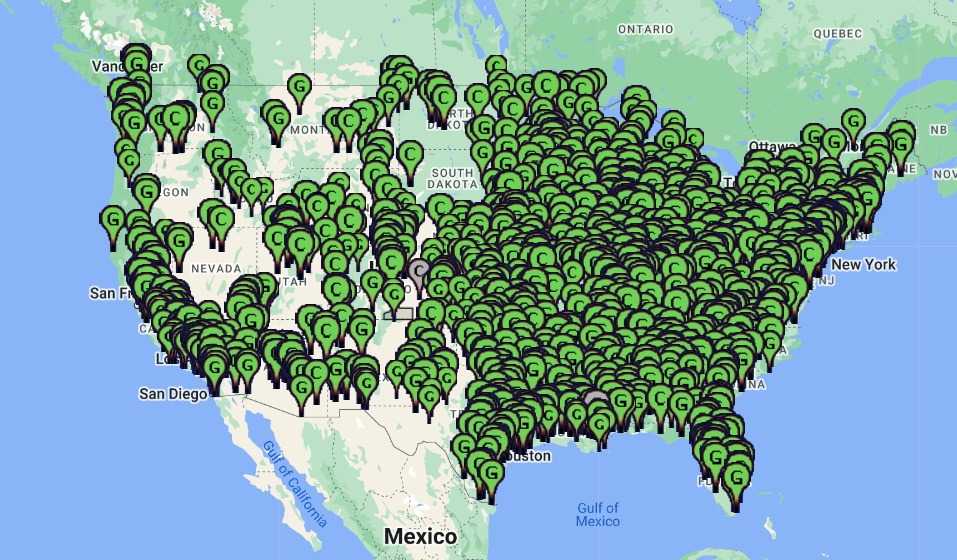

And so industry officials and others express skepticism about any link, even as they cooperate, to varying degrees, with researchers. Meanwhile, 334 disposal injection wells in Colorado pump wastewater deep underground, with companies currently seeking approval for 35 more — like one near Roy Wardell’s ranch in Platteville.

Wardell, 73, didn’t feel the earth shake on his 3,500-acre Weld County spread. But he’d been saying for a while that too many injection wells are concentrated near his property — five of them within a 2‑mile radius.

He opposed a permit for the newest proposed well after reading about seismicity concerns in Oklahoma, Ohio and Texas. And then Greeley was added to the list.

“I felt a little bit like a prophet, already voicing that concern before it happened,” says Wardell, who in addition to raising purebred Angus, draws oil and gas revenue from wells on his property. “You have to balance. Just because you might have some good income, you don’t want to throw away your health and safety and land. I felt the earthquake thing is much bigger than my place.”

He thought his concerns were heard by the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, the panel charged with both promoting and regulating the industry. But he was not surprised that the permit was granted.

“Colorado is ground zero”

Human-caused events — from mine explosions to nuclear tests to fluid injection — have rattled the state over decades, but it’s the last category that has particular resonance in these oil and gas boom times.

“Colorado is ground zero for research on induced earthquakes caused by injection,” says Bob Kirkham, a consulting geologist who formerly worked for the Colorado Geological Survey. “Yet still there are hundreds of injection wells that aren’t causing quakes. There must be something geologically that’s going on responsible for some causing earthquakes and some not, but we don’t know the answer at this time.”

When the Army began pumping liquid waste from its Rocky Mountain Arsenal chemical weapons plant in 1962, thousands of small earthquakes ensued, and a couple exceeded magnitude 5.0 — with one causing $1 million damage to nearby Commerce City.

When geologist David Evans took note of the seismic activity and eventually found a correlation between the number of quakes and the volume of injected liquid at a given time, the Army denied any connection. Other geologists also were skeptical about his findings until the U.S. Geological Survey launched its own study, which ultimately vindicated Evans.

That discovery led to the USGS teaming with the oil industry in the Rangely oil field in northwestern Colorado to determine if water injection, which seemed to be triggering frequent minor quakes, could effectively function as a seismic switch.

When injection stopped, dozens of earthquakes per day fell to fewer than 10. When it resumed, so did the frequency of seismic activity. The experiment was repeated several times into the early 1970s.

In the Paradox Valley, efforts to reduce salt content in the Dolores and Colorado rivers led to another closely watched experiment: The Bureau of Reclamation intercepted salty groundwater before it hit the Dolores and put it in evaporative ponds and, starting in 1996, injected it underground.

The bureau had copious pre-injection seismic data for comparison — there wasn’t much going on — and set up microseismometers to monitor data for years. Thousands of earthquakes have been induced, most so small they could not be felt.

“When they started to inject, they started having quakes right at the bottom of the well,” Kirkham says. “You could see where they started, how they migrated away from the well, found a fault zone and started using it as a place for epicenters.”

After a magnitude‑4.3 quake in 2000, they dialed back the injection rate with the desired result — no more activity over 4.0.

“If we know where that threshold is, you can continue to inject and not cause problems,” Kirkham notes. “It’s important to identify why certain areas are prone to injection-induced quakes and some aren’t.”

Debate over induced seismicity recently has played out in southern Colorado, where earthquake swarms near Trinidad — including a magnitude‑5.3 quake in 2011 — have produced differences of opinion over possible man-made or natural causes. The USGS contends that at least a majority of the quakes are related to wastewater injection, while industry people and the Colorado Geological Survey counter that such an assessment is premature.

USGS geophysicist Justin Rubinstein co-authored the study linking seismic activity near Trinidad and in Oklahoma to injection wells and now works in the agency’s Induced Seismicity Project.

He would love to see another study like the Rangely experiment in the ’60s, but notes that it would require a seldom-seen partnership between independent researchers and industry.

In the meantime, one of the main goals of the USGS project is to more fully grasp the hazards associated with injection.

“We can’t say there’s no risk of there being significant damage and loss,” Rubinstein says. “Trying to quantify that is an area of active research — one of the most important things we’re doing now.”

At magnitude 6.6, Colorado’s largest recorded earthquake shook a much less populous state in 1882. It took more than 100 years for scientists to dial in its natural origin. Kirkham and a colleague placed it about 10 miles north of Estes Park in a 1986 study that was later confirmed by USGS research.

Even today, experts note that there’s a good deal we don’t know about what lies beneath the state’s diverse landscape.

“We’re at the beginning stages of trying to understand the seismic activity in the state, even the faults we have,” says Matt Morgan, senior geologist at the Colorado Geological Survey. “There are about 90 faults that we know of with potential of slipping. But most of the events may occur on features that are unmapped.”

One proposal in search of funding would put dozens more permanent seismometers around the state, with data fed to the National Earthquake Information Center at the USGS. Within a couple of years, Morgan estimates, geologists would gain a better understanding of the forces at work across the state.

Among other things, it could assist in the creation of the seismic hazard maps produced by the USGS every six years. The most recent edition, released this summer, didn’t account for quakes that may have been induced, prompting some experts to question whether Colorado’s risk has been underestimated.

Mark Petersen, the national regional coordinator for the USGS Earthquake Hazards Program, says that while the maps sidestepped the issue of potentially induced earthquakes by ignoring them in this edition, plans are underway to factor them in.

Matt Lepore, director of the COGCC, notes that underground injection is the best disposal option available, distinguishing the process from recycling, which also has been on the rise. As the increased oil and gas activity has produced greater demand for disposal wells, it also carries the need to evaluate the capacity of the system.

“We need to get everything lined up in that respect,” Lepore says, “and make sure that there’s enough capacity to operate wells the way they’re permitted and designed to operate, which in our view keeps those risks at a reasonable level.”

Strong opinions

When William Yeck asked a landowner east of the Greeley airport for permission to put a small seismometer station on his property, he was told in no uncertain terms: Fracking doesn’t cause earthquakes.

Opinions tend to be firmly held — on both sides of the fracking issue — in an area where oil and gas production has become a major economic force as well as an environmental concern.

And while fracking and wastewater injection wells go hand in hand, experts distinguish between the process of hydraulic fracturing to extract oil and gas and the disposal of the produced water pumped deep underground — ideally to disperse into porous rock.

It’s this latter process that has become the object of scrutiny with regard to seismic activity.

Yeck, a doctoral candidate at CU, explained the rationale behind the study of the recent Greeley earthquake: It occurred in an unusual spot, and one hypothesis holds that the seismic activity may have been induced. By stationing equipment in the area to monitor activity, researchers could test the hypothesis.

The landowner consented, and Yeck buried a seismometer about a foot deep in farmland at the edge of a cornfield that looks out onto a flat expanse where workers attend to two drilling rigs.

A short distance away, trucks rumble into a wastewater facility that includes a well designated C4A — the injection well whose activity and proximity to the earthquake’s epicenter have made it a focal point of observation.

One August morning, Yeck parks near the portable station, clears some tall weeds that have sprouted around it and opens the green plastic, oblong box outfitted with a solar panel for power. He checks the data logger that acquires information from the seismometer, connects an iPod Touch to make sure the unit’s GPS settings and data configurations are correct, replaces the current data disk with a new one and does a “stomp test” — pounding his foot on the ground to make sure the instrument is reading ground vibrations.

On this unit, he also checks the cellphone modem that transmits real-time data that can be monitored by the oil and gas commission, the well operator and consulting companies, as well as the public. Only two stations among the six scattered around the quake area have that capability. Other data are retrieved at roughly two-week intervals.

The project, headed by CU geophysics professor Anne Sheehan, continues a revival of interest in the field of induced seismicity that has accompanied the surge in oil and gas production.

Before the Greeley quake, the most stunning research this summer had come from Oklahoma, where researchers — including two of Sheehan’s colleagues at CU — attributed a massive increase in seismic activity to injection wells, claiming that the pressurized wastewater seeped into faults and caused a spike in activity.

Oklahoma had averaged about two quakes of magnitude 3.0 or higher before 2008. In the first four months of this year, the U.S. Geological Survey recorded 145.

After the Greeley quake, Sheehan saw an opportunity to gather data related to seismic activity in the vicinity of the C4A well run by NGL Water Solutions.

“In other places like Oklahoma, seismicity is nearly out of control,” Sheehan says. “If that’s potentially what’s happening in Colorado, we want to nip it in the bud. If it’s related to a well, let’s figure out the parameters they can operate at safely.”

When the COGCC asked NGL to stop injection after a magnitude‑2.5 quake June 23, researchers had the opportunity to look at seismic activity while the well was dormant and later as regulators authorized the company to resume injection at lower but gradually increasing rates.

The commission gave the OK to resuming injection of wastewater at C4A on July 18. But instead of 17,000 barrels per day, NGL could inject only 5,000 barrels per day for 20 days. On Aug. 7, that volume increased to 7,500 barrels per day — all at the same maximum injection pressure.

If all continues to go well, the commission anticipates authorizing NGL to push the volume to 10,000 barrels per day, with room for later negotiation if the rock proves porous enough to accept wastewater easily.

The CU study will continue to measure seismic activity in the area until winter, but so far it has detected hundreds of small earthquakes of a magnitude generally below the “felt range” that correlate to the location of the well.

Only four have been recorded over magnitude 2.0, most recently a magnitude‑2.1 on Aug. 13. The COGCC has continued to monitor activity and could halt injection again if quakes of 2.5 or above occur within a 2.5‑mile radius of the well.

But while significant activity has been quiet recently, Yeck notes that induced seismicity in part depends on the core pressure in the rock where injection has been taking place. That pressure would dissipate when injection is stopped, but once injection is resumed, it could take a while to repressurize the system.

Since the shutdown and restart, seismicity rates have not increased. One factor could be action taken by NGL to seal part of the well with a cement casing to alter the path of injected water away from so-called “basement” rock.

“At the moment, it looks like it may have worked, because the earthquakes are very small,” Sheehan says. But it could also be that in two months’ time, there’s going to be enough fluid that earthquakes will start up again.”

In the meantime, the COGCC’s Lepore says the commission’s stance on any connection between the Greeley quake and the injection well remains in the “not definitively caused by” category.

“I think we have responded in a way that we feel is appropriate, and we’re happy with the results so far,” Lepore said. “We’ll stay on the path we’re on unless new data emerges.”

NGL, which owns 10 wells at seven facilities in eastern Colorado’s Denver-Julesburg Basin with plans to add seven more wells at five new Weld County facilities in the next 18 months, has been a willing partner to the study. And while NGL senior vice president Doug White says he’ll leave the science to the experts, he stands by the practices that have worked for his company.

“We have wells that have been injecting water for 20 years with no issues,” White says. “Until we see definitive scientific data that connects the two, we’re business as usual based on how we’re regulated by the oil and gas commission.”

Anadarko Petroleum Corp., which uses both its own wells and other commercial wells for disposal, pointed out that injection wells are regulated, tested frequently and have limits on their volume and pressure.

“Though some studies have shown injection can cause induced seismicity, the magnitude is similar to a train passing by well below the surface of the earth,” Korby Bracken, director of health, safety and environment for Anadarko Rockies division, wrote in an e‑mail. “…With adequate regulation already in place, water disposal wells have been utilized for many years, by many industries, safely and effectively.”

The CU researchers remain cautious in drawing any conclusions until the study is completed, peer reviewed and published. Eventually, the CU hydrologists who aided the Oklahoma study will use the data, as well as other information about the permeability of the geologic formations in the area, to run computer models showing where the injected fluids could migrate over time.

Meanwhile, Coloradans wait for definitive word on underground rumblings that, depending on point of view, merit a shrug of the shoulders or instill a sense of foreboding.

“Of course it’s a concern, but by and large we believe it’s one that can be managed,” says COGCC’s Lepore. “You know when you go out there, there are risks. But you try to be prepared and understand those risks and anticipate and avoid them. How we handle the C4A well reflects how we handle what we believe is a manageable situation. ”

Kevin Simpson: 303–954-1739, ksimpson@denverpost.com or twitter.com/ksimpsondp