– by Bob Berwyn, July 7, 2014, The Colorado Independent

Even here, in a cool forest hollow near Tenmile Creek, you can feel the tom-toms.

It’s a distant beat, born in the marbled halls of Congress, where political forces blow an ill wind across Colorado’s forests. Nearly every Western elected official with a clump of shrubby cottonwoods in his or her jurisdiction claims to be a forest expert. And when senators and congress members make forest policy, rhetoric usually trumps science — as is the case with laws requiring new logging projects that may wipe out some of the very trees needed to replenish forests in the global warming era.

The drumbeat of support for logging is a political response to the threat of a forest health crisis that no longer exists, and maybe never did.

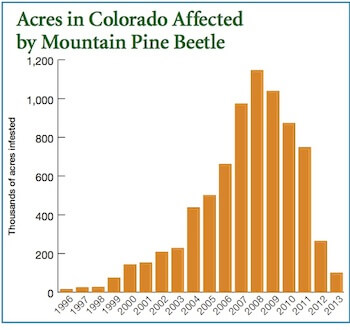

Showing their natural resilience, Colorado forests are bouncing back from the pine beetle outbreak that peaked between 2007 and 2009, when the bugs spread across a mind-boggling 1 million acres of forest each year. But by last year, bug numbers dropped back to natural levels — just enough to take out a stand of sick, old trees now and then. Contrary to the spin out of D.C., it’s nature’s way. After all, pine beetles are no foreign invaders. They evolved with lodgepoles over millions of years to drive forest death and rebirth.

But there are a lot of dead forests out there. And so Congress — partially at the urging of Colorado’s two Democratic senators, Mark Udall and Michael Bennet — ordered the U.S. Forest Service to designate about 9.6 million acres of National Forest lands across Colorado for expedited logging to battle insects and disease. The fast-track means less environmental review — and could mean logging on a scale not seen since the old timber quota days, when Forest Service success was measured by how much timber it produced.

The forest for the trees

The new law, along with a slew of similar measures passed since 2003, could do more harm than good, some forest scientists say. A nuanced vision of the delicate balance of forest ecology doesn’t help when you’re stumping for votes by pushing logging projects under a jobs banner, or as a “do-anything” political response to a crisis like a wildfire topping the evening news. Nevertheless, a wrong-headed implementation of new logging plans may impede long-term forest recovery and adaptation to a changing climate.

“We may be cutting down the very trees we need to save the forest,” said Diana Six, a Montana-based U.S. Forest Service biologist who studies bugs and trees right down to the genetic level.

Along with the salvage harvest of dead trees, many of the logging projects authorized under federal emergency forest health laws also cut down trees that have survived. Those trees may hold the genetic key to the future of Colorado’s forests, Six said.

“It’s natural selection. The bugs wiped out the trees that are not adapted to current conditions … Underlying genetics will determine future forests,” she said, challenging the conventional wisdom that logging is needed to restore forest health.

From an economic standpoint, logging beetle-killed lodgepole pines rarely yields a profit. In fact, many projects in Colorado are subsidized. Overall, the U.S. and Canadian governments have spent millions of dollars on massive logging projects aimed at directly trying to halt the spread of the bugs, with no signs of success on a meaningful scale, Six said.

Besides, Colorado forests are re-growing just fine on their own, according to the latest Forest Service research from the 23,000-acre Fraser Experimental Forest in Grand County — the perfect place to monitor, near the beetle outbreak’s ground zero in Colorado. The Fraser forest already has delivered a huge amount of baseline information about forest conditions. As the pine beetles killed most of the lodgepole pines in the forest during the early 2000s, the scientists were able to measure how the infestation affected runoff and water quality. In the aftermath, they could compare how well the forest is coming back both in logged and unlogged areas.

Where beetle-killed trees have been logged, the forest is once again growing mainly as lodgepole. In some places, big aspen groves are developing and some areas that were covered with slashed wood debris just a couple of years ago have regrown as grassy meadows.

In areas where the dead trees were left standing, subalpine fir trees are popping up in healthy clumps, adding diversity to the larger forest mosaic.

There’s also little evidence that beetle-killed trees have been a big factor in many of the recent western megafires, which have burned in all different types of forests. Specifically in Colorado, detailed post-fire reports show that the pine beetle epidemic was NOT a main cause of the destructive conflagrations along the Front Range in the last several years.

Still, in the policy arena, the drumbeat for more logging continues in the name of forest health, wildfire mitigation and watershed protection — despite little science to show that it’s effective.

Forest stories

The fact that the pine beetle infestation is more or less over for now doesn’t change the impressive scale of the forest die-off, which is unprecedented in recorded North American history. Or the fact that spruce forests in southwestern Colorado are now in the grips of a different insect — the spruce beetle — which may eviscerate forests on a similar scale as the pine beetle. Or that tiny ips beetles, during the early 1990s, wiped out up to 75 percent of the iconic southwest Colorado piñon pines, which, in many areas, show no signs of growing back. Aspens also took a bit hit after a series of warm and dry years in the early 2000s.

The scale and timing of the forest die-offs suggest that they are only symptoms of a deeper pathology linked with Colorado’s warming climate. Although everybody agrees on the need to trim, cut and crop back dead wood and flammable brush near homes and valuable property, logging on a mass scale is probably not the answer to the state’s forest woes. Historically, the only thing that stops the pine beetles are severe winter cold snaps, which aren’t likely to happen again anytime soon, according to climate scientists.

“In order to have adaptation, it’s all genetics,” Six said, explaining that scientists are trying to figure out why some trees in hard-hit areas survived the wave of bugs.

“A lot of us had no idea what was going on. Then a pattern started to stand out. In these forests stands where some trees survived, they had strikingly different growth rates.”

The tree rings showed that some of the trees are genetically adapted to survive in warmer and drier times, while others do better in a cooler and wetter climate. Logging that disturbs the natural rhythm on a significant scale possibly disrupts the ability of forests to reseed themselves with trees that are genetically suited to the era of man-made global warming, Six said.

Forest conditions alone don’t cause massive insect outbreaks, and there’s no evidence at all that logging now will prevent future outbreaks. There has to be a trigger, and for the bugs, it’s usually heat and drought that not only weaken the trees, but speed up the life cycle of the insects.

The U.S. and Canadian governments have spent hundreds of millions of dollars in direct control efforts. In Canada, the beetle populations also erupted on an epic scale, and they’re now moving east through a new species, jackpine, with nothing to suggest the insects will stop until they’ve swept to the East Coast along Canada’s transcontinental forest belt.

But so far, officials in both countries haven’t been able to offer any assessments of how effective their treatments are, Six wrote in a January 2014 paper, published in the Forests journal.

“The on-the-ground reality is that direct control efforts typically fall far below the levels needed to stabilize, let alone control mountain pine beetle populations,” her study found.

Time travel

To learn why politicians are still calling for logging, travel back in time to 1997. Most of Summit County’s forests were still lush green, when Tere O’Rourke, an eco-savvy local district ranger for the U.S. Forest Service saw signs of the impending pine beetle attack in the lodgepole forests of Summit County. She tried to raise the alarm, calling for holistic and early treatments, including prescribed fire, to get ahead of the curve.

Nobody listened.

Ten years later, residents and visitors all through Colorado’s north-central mountains were dumbstruck at the scale and speed of the forest die-off. Seemingly overnight, huge stretches of the mountain landscape were stained red by the beetle blight. By then, it was pretty clear that the trademark lodgepole forests of north-central Colorado would be all but wiped out, changing the face of popular mountain playgrounds for decades to come.

It’s debatable whether early intervention would have made a difference. Bug and tree scientists had seen it before. An outbreak in the early 1980s also killed big areas of lodgepoles across regions overlapping with the current forest die-off. But the ferocity of the beetle attack this time around took everyone by surprise.

At the height of the outbreak, around 2006, you could stand in a green lodgepole grove in the summer and listen for the high-pitched raspy sound of millions of tiny insect jaws chomping through the flesh of the trees. A year later, every tree was dead and red — so remarkably and uniformly distinctive that unknowing visitors to Summit County inquired as to the unusual species of orange pine trees.

Emergent forests

It took a while for the forest health meme to emerge. Gradually, mountain communities grew nervous at the ominous sight of vast stands of gray skeleton trees crowding next to million-dollar vacation homes. Water and power companies claimed the die-off could threaten power supplies and water deliveries.

By the time Congress started passing so-called forest health laws in 2003, it was much too late to do anything but cut and haul away dead wood that was barely strong enough for fence posts. All the talk amounted mainly to a lingering, hand-wringing forest death watch, with vague plans for restoration, logging and the “future forest.” Clearly, dealing with the spindly greying lodgepole toothpicks wasn’t high on the agenda.

The forests laws that were passed put the U.S. Forest Service on a questionable path of shortcutting environmental reviews for logging on big tracts of national forest lands, according to conservation groups who tried to slow the congressional rush to more tree cutting.

And now, with the insect epidemic waning, research by forest scientists suggest that those politically motivated logging projects are the “wrong choice for advancing forest health in the United States,” Six said.

She’s not the only one to question the wisdom of pushing more backcountry logging in the name of forest health. There are several studies showing that Congress is barking up the wrong tree and diverting precious budget dollars away from clearing forests where it’s really needed — within a few hundred feet of homes.

“The science is clear. Unless preventive measures are aimed at creating defensible space around homes, the federal government will be shoveling taxpayer money down a black hole,” said Dominick DellaSala, a forest researcher who works on behalf of conservation groups.

“Logging in the backcountry will do little to prevent insect infestations or reduce fire risks, and it will not solve Colorado’s concerns over dying trees,” he said.

“Fires in lodgepole pine and spruce-fir forests, such as those found in Colorado, are primarily determined by weather conditions,” added Dominik Kulakowski, a professor of geography and biology at Clark University in Massachusetts. “The best available science indicates that outbreaks of bark beetles in these forests have little or no effect on fire risk, and may actually reduce it in certain cases,” said Kulakowski, who has been researching the interactions between bark beetle outbreaks and forest fires in Colorado for more than a decade.

“Drought and high temperature are likely the overriding factors behind the current bark beetle epidemic in the western United States,” said Scott Hoffman Black, executive director of the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation and lead author of a 2012 forest health report. “Because logging and thinning cannot effectively alleviate the overriding effects of climate, it will do little or nothing to control these outbreaks.”

“It’s not worth thinning on a broad landscape level, especially in roadless areas,” said Barry Noon, a wildlife ecologist at Colorado State University. “The ecological cost is too high.”

According to Six, many forest health logging projects are not based on science, but on the human need to feel in control over nature. But making choices on that basis “might lead us to act to respond to climate change before we understand the consequences of what we are doing, in the end producing more harm than good,” she concluded.