By Christian Davenport

Austin American-Statesman Staff

April 16, 2000

Original articles (were) online at: http://www.austin360.com:80/news/1metro/2000/04/16pipelines_001.html

Though empty now, warning signs mark the route of the Longhorn pipeline as it runs near homes in the Circle C neighborhood in South Austin. Plans to use the pipeline to move gasoline and jet fuel worry environmentalists and residents. ‘If it spills (over the aquifer), it will reach Barton Springs,’ said Nico Hauwert, senior hydrogeologist for the Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer Conservation District.

Photo by Mark Matson/for AA-S

Several lines cross Central Texas, but they go unnoticed — until an accident happens

They are three feet below the surface, a labyrinth of steel veins that pump oil and gasoline from one end of the country to the other under houses, schools and rivers. Although they carry hazardous materials, the nation’s pipelines are undoubtedly the safest way to transport the products that modern society depends on to fuel cars, heat homes and light stoves.

But sometimes pipelines leak. And although most spills are quickly cleaned up before they pose any threat, others kill people and wildlife, contaminate public drinking water sources and set off spectacular explosions that send towers of flames and smoke into the air.

Last year, pipeline accidents in the United States killed 21 people, injured 106 and caused nearly $100 million in property damage. And no place in the country has more pipeline accidents than Texas.

In Central Texas, the pipelines crisscross north to south and east to west through the heart of Austin, taking paths under Town Lake, the Colorado River, and countless homes.

Yet in the debate over whether the Longhorn pipeline can be reopened to pump gasoline 700 miles from Houston to El Paso, the rest of the massive spaghetti-like system of pipelines has been virtually ignored. So has the pipeline industry’s history of spills; there have been about 6 million gallons of spilled material a year for the past decade — the equivalent of an Exxon Valdez spill every two years.

Right now there are hundreds of thousands of miles of pipelines carrying hazardous materials across Texas. Currently, two operating lines follow virtually the same route as Longhorn, which has been dormant since 1995.

Those lines are seldom mentioned.

“It’s a classic case of out of sight, out of mind,” said Bob Rackleff, the head of the National Pipeline Reform Coalition. “These pipelines are underground where nobody thinks about them.”

If it weren’t for a group of Hill Country ranchers, the Longhorn project could have been just as anonymous. The ranchers’ lawsuit, paid for by one of Longhorn’s competitors, prompted a federal judge to order a review of the pipeline. Since then, Longhorn’s opponents have focused on the integrity of the 50-year-old pipeline, its record of 60 spills, and the threat it could pose to the houses and schools along its path.

Now, a year and half later, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Department of Transportation are expected to decide whether the Longhorn pipeline, once used for crude oil, can be reopened. That decision could come as early as this week.

Meanwhile, Congress is deciding what to do with the federal agency that oversees pipelines, the Office of Pipeline Safety. A pipeline explosion in Bellingham, Wash., that killed three boys prompted U.S. Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., to file legislation that would give states more power in inspecting pipelines. And last week, Vice President Al Gore introduced the Pipeline Safety and Community Protection Act of 2000, which would increase safety measures and inspections in densely populated and environmentally sensitive areas.

The Office of Pipeline Safety has 55 inspectors nationwide, including 10 stationed in Houston who are responsible for the pipelines in Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Arizona and Louisiana.

Pipeline critics such as Rackleff say pipeline problems are a result of a lack of governmental oversight, aging lines that corrode and break, and cities and suburbs that continue to build directly over pipelines.

But the industry says there is no safer way to transport petroleum products than by pipeline, and the amount spilled is just a sliver of what is transported safely.

“We do just about everything humanly possible to ensure that the system works at its best,” said Daphne Magnuson, a spokeswoman for the American Gas Association. “There is no way to guarantee zero risk, but that’s what we’re working toward.”

Dallas-based Longhorn Pipeline Partners — owned by a group of companies that includes Exxon Mobil Corp. and BP Amoco — say the pipeline has been one of the most scrutinized pipelines ever and is one of the safest in the country.

“From day one, since we’ve taken over this pipeline, our whole focus has been on upgrading and improving this pipeline,” said Longhorn President Carter Montgomery. “If you look at the record of the pipeline business, an incident is the exception, not the rule.”

Chance of spills

Texas has more than 250,000 miles of pipeline that carry natural gas, crude oil and other refined products. The state has more miles of pipeline than any other state, and Texas has about one-sixth of all the pipelines in the country. Between 1984 and 1999 there were 1,654 accidents, which killed 46, injured 339 and caused nearly $138 million in damage.

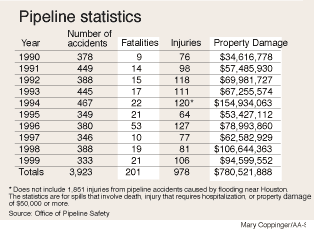

In the past 10 years, an average of 392 spills occurred each year nationwide, or more than one spill per day, according to the Office of Pipeline Safety. During that time, pipeline accidents killed more than 200 people, injured nearly 1,000 and caused more than $780 million in property damage.

In 1992, more than half of the oil spilled in the United States — 52.5 percent — came from pipelines, according to a report in the Oil & Gas Journal, a trade magazine.

Engineers Diane Hovey and Edward Farmer wrote an article in that publication last year about the likelihood of “reportable” spills — those involving a death, an injury that requires hospitalization or property damage of $50,000 or more.

“The unavoidable statistical truth is that even short, simple pipelines will have a reportable spill during a 20-year lifetime,” they wrote. “Operators of long pipelines (1,000 miles of pipeline) can expect a reportable accident every year. In essence, if you operate a pipeline you are going to have an accident.”

Many fear that a spill in Austin would be disastrous. The city estimates that 60,000 Austin residents live within one mile of the Longhorn line and that there are 15 Austin schools within 1.5 miles of the line.

The pipeline crosses the Edwards Aquifer and the Colorado and Pedernales rivers, all of which supply Austin and Central Texas with drinking water. The line would carry gasoline and jet fuel, which unlike oil or natural gas would move quickly if spilled through the catacombs of the aquifer. The gas would contain MTBE, a dangerous additive that dissolves in water and is possibly a human carcinogen.

“There would be a whole lot of product coming out of that line at a high pressure,” said Nico Hauwert, senior hydrogeologist for the Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer Conservation District. “If it spills (over the aquifer), it will reach Barton Springs.”

In recent weeks, U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett, D-Austin, and Texas Land Commissioner David Dewhurst have questioned the safety of the pipeline and have asked the EPA to study it further. Dewhurst also threatened to withhold granting the pipeline easements across state land until he is convinced it is safe.

Safety measures

Longhorn says its line is safe.

The company points to a preliminary study conducted for the EPA that concluded that its pipeline will have “no significant impact” on the environment or human safety as long as Longhorn completes 34 “mitigation measures.” The company has agreed, for example, to frequently inspect pipeline segments in populated or environmentally sensitive areas. It will also perform periodic internal testing of the line to test its strength and detect flaws and cracks; replace the old pipe over the Edwards Aquifer with new, thicker-walled pipe; and install a special leak-detection and control system over the aquifer.

“We’re putting up signs and leak-detection systems,” Montgomery said. He added that federal agencies “reached a conclusion of ‘no significant impact’ because of the mitigation we agreed to do.”

The company has studied “the integrity of the pipeline, which is more important than the age,” Montgomery said. “We’ve tested it, we’ll test it again before it opens, and we will continue to test it after we are in operation.”

A report for the American Petroleum Institute found that an accident involving an oil truck is 87 times more likely than a pipeline accident. Replacing a pipeline that pumps 6.3 million gallons a day would require a fleet of 750 trucks, according to the report.

Another report found that in the past 30 years the number of oil spills decreased by 40 percent, from an average of 318 spills to 197, and the volume of spills decreased by 60 percent, from 14.8 million gallons to 5.8 million. The number of oil spills has decreased during the past four years, as well, from 195 incidents in 1996 to 149 in 1998.

“This is a big system; it moves lots and lots of oil,” said Ben Cooper, the executive director of the Association of Oil Pipelines. “The question is, what’s the lowest level of leaks you can get to? The trend is down, and that’s what you’d expect as time goes on and you get better technology. We have 44,000 people killed on the highway every year, so we’ve developed air bags and seat belts and safer cars.”

The industry also points to data that show that a leading cause of pipeline accidents is outside forces, such as construction crews who dig without knowing a pipeline is underneath them.

Magnuson said the natural gas industry spends about $2 billion a year on safety programs and has spent much of its resources promoting a 1998 law that requires construction crews to call a hot line that lists the locations of pipelines.

“There is an incredible amount of construction going on and fiber-optic cable being laid,” Magnuson said. “If we can cut down on third-party damage and get a program in place that will improve communication among the people out there digging and the pipeline companies, I think we’ll go a long way in making our safety record even better.”

Deadly accident

Soon after the calls started flooding all 10 of Kaufman County’s 911 lines in August 1996, Don Lindsey, the county fire marshal and emergency coordinator, told his staff to set up for mass casualties.

A pipeline carrying liquid butane had broken near the town of Lively, southeast of Dallas, and it was gushing out with such force that “you could hear the hissing from miles away,” Lindsey said.

The smell prompted people to evacuate their homes, and it made Danielle Smalley, 18, sick to her stomach as she was packing her bags for college. She told her father that she and a friend, Jason Stone, 17, would drive into town to report the odor to county officials because their home did not have a phone.

When their car drove into the butane vapor cloud, it exploded.

“It was like you dropped a napalm bomb; everything was charred,” said Lindsey, who is now retired. “There was a flash, and then there was nothing left. It killed everything. There was not a bird chirping or a grasshopper making a noise. You just stood and looked, and the grass was gone, and all there was was a few burning timbers. It was just pure black.”

Smalley and Stone were killed instantly.

But the fire burned for 37 hours.

In its report after the accident, the National Transportation Safety Board concluded that the leak was caused because the line had corroded. And the report said: “Because no overall requirement exists for (pipeline) operators to evaluate pipeline coating conditions, problems similar to those that occurred on this pipeline could occur on other pipelines.”

A 1993 report in the Oil & Gas Journal concluded that older lines are more likely to corrode and leak. A 1,000-mile line, for example, has a 22 percent chance of leaking because of corrosion within one year and a 99 percent chance of leaking within 20 years, according to the study.

Still, most accidents occur when construction crews break the underground lines.

That’s what happened in 1979 to the Longhorn, which at the time was owned and operated by Exxon and carrying crude oil. A construction crew was digging a ditch for a water line in South Austin when it hit the pipeline. About 46,200 gallons spilled, and 41,160 gallons were cleaned up along Ft. Sumter Road. Then, a few years later, residents in the area started calling the city to complain that their tap water smelled like gasoline.

“When you turned the water on, you could smell it and taste, and you knew that’s what it was,” said Jack Gatlin, acting director of field operations for the city’s water utility. He said constituents of the oil had “seeped through” the residents’ water pipes, but nobody got sick. “They called the water department because they were scared to drink the water, and rightly so.” The city replaced the pipes with stronger ones, he said.

The Longhorn pipeline broke again in 1987 after it was hit by a contractor. This time about 48,300 gallons of oil spilled near the intersection of Brodie and Slaughter lanes, near the Circle C subdivision.

Nobody was injured, and the spill, like many others, garnered little or no media attention and was forgotten.

That was the case with most of the 60 spills from the Longhorn pipeline. There were 12 spills of at least 50 barrels — or 2,100 gallons — or more from the pipeline and 48 spills from pumping stations, according to a study commissioned by the EPA.

In 1998, a segment of the Longhorn pipeline near Houston exploded during a test for faults, slightly injuring one worker.

Just in the past few weeks, there have been several major pipeline spills across the country, two of which were in Texas.

• On April 8, 111,000 gallons of fuel oil spilled into the Patuxent River, a tributary to the Chesapeake Bay, in southern Maryland. A couple of days later, it had spread for 5 miles down the river, killing wildlife but posing no threat to humans.

• On March 22, a natural gas pipeline exploded southeast of San Antonio, sending flames high into the air and blasting a hole in U.S. 181. No one was injured.

• On March 10, about 500,000 gallons of gasoline spilled into a creek that runs into Lake Tawakoni, which provides Dallas with 25 percent to 30 percent of its drinking water. Small levels of MTBE were found in the lake where the creek enters it, said David Bary, a spokesman for the EPA. Dallas has stopped taking water from the lake, and the city will spend $12 million to build a new pipeline to another water source.

• On Feb. 12, authorities found that a pipeline had leaked as much as 600,000 gallons of oil through a hole the size of a pencil eraser in Delaware. They said the pipeline had been leaking undetected for eight to 12 years.

Such safety issues are not new.

Same problems

In the East Texas town of Devers, four people died when the car they were in drove into, and ignited, a vapor cloud after a backhoe had hit a pipeline, which was carrying a liquid mix of ethane and propane. In a press release a year after the accident, the National Transportation Safety Board said it “demonstrated the need for faster action by the U.S. Department of Transportation on a series of pipeline safety recommendations dating back more than five years.”

That was in 1976.

Nearly 25 years later, the safety board is still criticizing the federal government for failing to properly regulate pipelines and implement important safety measures.

Testifying before Congress last year, Jim Hall, the safety board chairman, said a “lack of action” by the Research and Special Programs Administration, which is part of the Office of Pipeline Safety, “continues to place the American people at risk.” He said the agency has one of the worst records in implementing NTSB safety recommendations, 68.9 percent, and that several such recommendations made in 1992 are still not implemented. He told the Boston Globe last year that he’d give the Office of Pipeline Safety “a big fat F on everything they’ve done.”

Lois Epstein, an engineer with the Environmental Defense Fund who sits on the federal advisory committee that oversees pipelines, said “pipelines are one of the last frontiers of environmental protection because so many other environmental threats have been addressed. But pipelines haven’t been at all.”

Kelley Coyner, head of the Research and Special Programs Administration, said at a press conference last week that that is about to change.

“This summer we will see a major overhaul of our safety standards,” she said. “The pipeline safety legislation that the vice president has proposed raises the level of resources not only for the federal government but for the state governments to make sure pipelines are safe.”

And she said the agency would “work on how we protect pipelines from outside force damage. That is a shared responsibility of the companies and the communities around the pipelines. We have to crack the nut of how we deal with corrosion.”

The budget of the Office of Pipeline Safety doubled from $16 million in 1995 to $32 million the next year, when a propane gas leak in San Juan, Puerto Rico, led to an explosion that killed 33 and injured 69. Its budget for this year is $36.7 million.

This year the law that allows Congress to fund the agency expires, and politicians, such as Gore and Murray, are discussing how the agency should operate. Michele Joy, the general counsel of the Association of Oil Pipelines, said the industry was still “in the process of digesting” the proposal and has not yet taken a position.

But overcoming the influence of the oil and gas lobby may be difficult. The industry gave more than $22 million in the 1998 congressional election, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Enron Corp., which is one of Gov. George W. Bush’s leading contributors, gave more than $1 million. U.S. Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison and U.S. Reps. Joe Barton and Kay Granger were among the top recipients of the industry’s donations. Barton is the chairman of the House commerce subcommittee on energy and power, which already approved legislation reauthorizing the Office of Pipeline Safety.

Gore’s proposal is similar to the legislation filed in January by Murray, the Washington senator, because it would give the states more authority to inspect pipelines.

In most cases only Office of Pipeline Safety inspectors can inspect interstate lines. The states are responsible for those lines that stay entirely within their borders. In 1996, Carole Keeton Rylander — who at the time was chairwoman of the Texas Railroad Commission, the state agency that oversees intrastate pipelines — asked the Office of Pipeline Safety if her office could inspect those lines that cross state lines. Texas has 30 inspectors.

But the pipeline agency denied that request. And recently it also told Arizona and Nevada that they could no longer inspect their interstate lines.

“It makes no sense whatsoever,” said Terry Fronterhouse, Arizona’s chief pipeline inspector and president of the National Association of Pipeline Safety Representatives, which represents state pipeline agencies. “The states are the ones who should be able to do it, and here’s why: The states have the people on board to do the inspections. The state people know more about what’s going on with the pipelines because the state people are all over the state on a daily basis. We have 11 inspectors in Arizona; they have zero.”

Under Gore’s plan, fines for spills would be increased from $25,000 to $500,000. Bush has not proposed a specific pipeline safety plan, but a spokesman said Bush believes the federal government should work closely with state and local officials on the issue.

Gore’s announcement follows one of the largest civil fines ever under the Clean Water Act. In January, Carol Browner, the administrator of the EPA, announced that the agency had reached a $35 million settlement with Koch Industries, one of the largest pipeline companies in the country. The EPA had sued Koch for pipeline spills that polluted waterways in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Alabama, Louisiana and Missouri.

There were 106 spills in 28 Texas counties from 1990 to 1997. Texas will receive about $17.5 million of the settlement to help clean up oil spills and protect coastal waterways, bays and estuaries vulnerable to pollution.

American-Statesman Washington Staff writer Jeff Nesmith contributed to this report.