Geology and Markets, not EPA, Waging War on Coal — Clean Energy Action shows that it’s the peaking of coal production, not Obama policies, causing coal’s decline by driving up the cost of extracting coal (June 2014)

Warning: Faulty Reporting on U.S. Coal Reserves — 2013 Clean Energy Action report on peaking of coal reserves

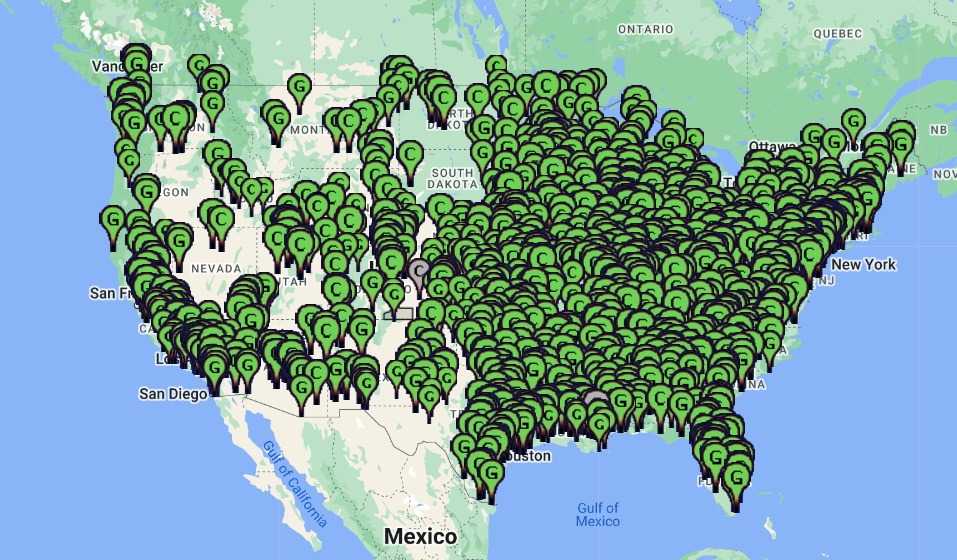

For decades, the United States has relied heavily on coal to meet its electricity demand. Coal accounts for approximately half of all US power generation. It is mined in 26 US states, burned in all but two (Vermont and Rhode Island), and its waste (ash) is disposed of in more than 600 dumps in at least 47 states. All told, there are upwards of 600 existing coal plants in the United States and thousands around the world.

Coal’s place in the America’s energy future is under attack and more precarious than ever.

The industry is under attack as it threatens our health, strains our economy, and is recognized as a driving force behind climate change and ecological destruction.

Health Impacts of Coal

Coal presents a serious threat to the safety of a community; threatening both water bodies (including drinking water) and air quality.

Health Impacts & Coal Mining: There are several types of coal mining and they are all unsafe for workers and communities. Underground mine workers often suffer from ‘black lung’ or pneumoconiosis. Workers get black lung disease from breathing in coal dust– it results in shortness of breath, and puts individuals at risk for emphysema, bronchitis, and fibrosis. Surprisingly, black lung is now on the rise among coal miners. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) reported that in 2005–2006, 9 percent of miners with 25 or more years of mining experience tested positive for black lung. That is in contrast to only 4 percent in the late 1990s. Black lung is incurable, increasing in severity, and is now hitting younger miners as well as more experienced miners.

Beyond posing threats to workers’ safety, pollution from coal-mining is linked to chronic illness among residents in coal mining communities. Data collected in a 2008 study by the WVU Institute for Health Policy Research shows that people living in coal mining communities:

- Have a 70 percent increased risk for developing kidney disease.

- Have a 64 percent increased risk for developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) such as emphysema.

- Are 30 percent more likely to report high blood pressure (hypertension).

The same study concluded that mortality rates are higher in coal-mining communities than in other areas of the country or region and that there are 313 deaths in West Virginia from coal-mining pollution every year. The study accounted for restricted access to healthcare, higher than average smoking rates, and lower than average income levels.

Mountaintop removal (MTR) mining, the mining practice of removing the tops of mountains to access (often) small seams of coal hundreds of feet below the surface, often contaminates water bodies. When mountains in Appalachia are literally blasted apart with ammonium nitrate (ANFO), the “overburden” rocks, soil, and debris above the coal seam, are pushed into valleys, burying, and often contaminating streams and other water bodies. Rock previously deep underground naturally contains toxic metals; when exposed and then dumped into water bodies, these metals can seep into streams, kill aquatic life, and contaminate drinking water sources.

Movies such as Coal Country illustrate visibly contaminated tap water in Appalachia communities such as Rawl, WV.

Health Impacts & Coal Plants: There’s no shortage of data to show that individuals living near a coal plant are at higher risk for health problems than those who do not live near a plant. In Delaware, years after residents requested a study, the Delaware Division of Public Health confirmed a cancer cluster in the six zipcode area surrounding NRG Energy Inc.’s Indian River coal plant. The study showed a cancer rate 17 percent higher than the national average.

In Chicago, where two aging coal plants sit in the majority-Latino neighborhood of Little Village, residents have reported respiratory problems for years. The Fisk and Crawford plants in Chicago have not upgraded their pollution control equipment, and instead have been exempted from federal pollution control standards under the Clean Air Act. Now the Clean Air Task Force attributes close to 350 deaths annually to the two outdated plants.

And near Longview Texas, the Martin Lake coal plant is responsible for 13 percent of all industrial air pollution in the state, contributing to Dallas-Fort Worth’s high ozone levels and non-attainment status.

Similar health problems plague every community downwind of a smokestack. Given that coal plants contribute 67 percent of sulfur dioxide (SO2), 23 percent of nitrogen oxides (NOx), and 34 percent of all mercury emissions in the nation, it is not surprising to notice increased rates of asthma, cardiovascular disease, and pre-mature and low birth-weight births in these communities. Emissions tests at coal plants have revealed 67 different air toxics. Fifty five of these toxics are neurotoxins or developmental toxins. Twenty-four are known, probable, or possible carcinogens. The Clean Air Task Force’s updated “The Toll From Coal report (2010) estimates that particulate pollution from existing coal plants would cause 13,200 deaths in 2010. The analysis found that the fleet of coal plants would also emit pollution resulting in more than 20,000 heart attacks, 9,700 hospitalizations, and more than 200,000 asthma attacks.

These coal-plant related health risks are unequally distributed across the population. In the United States, coal’s health risks affect African Americans more severely than whites, largely because a large portion of African Americans live close to coal plants and coal waste dumps. Sixty-eight percent of African Americans live within 30 miles of a coal plant, as opposed to 56 percent of whites and though African Americans comprise 13 percent of the (US) population, they account for 17 percent of the population living within 5 miles of a power plant waste sites. Asthma attacks triggered by exposure to above-average pollution levels send African Americans to the emergency room at three times the rate of whites. Hospitalizations and deaths from asthma are also higher among African Americans, likely exacerbated by restricted access to healthcare that could offer individuals preventative care. Children, the elderly, those with respiratory disease(s), and meat eaters (particularly seafood) are most vulnerable to the health risks coal burning poses.

Check out our page on Coal Ash for information on the health impacts of these toxic dump sites.

The Economics of Coal

Propped up by subsidies and campaign contributions, coal may not be viable for long. An economic analysis of the industry is revealing that coal is not cost competitive in the long-term, and may not even be right now. The coal sector also doesn’t provide the economic benefits, such as jobs, that the industry claims.

Coal has been booming in Appalachia for decades, yet it is one of the poorest areas in the country. Shouldn’t all of that coal-mining activity have made the residents and miners rich? One recent study compared poverty rates in WV coal-mining counties to poverty in WV counties without mining. The data showed that coal-mining communities were more impoverished than counties outside the coalfields, and the trend appears to be getting more pronounced. And though mining production has increased in West Virginia, mining jobs dropped nearly 30 percent (Source: Sierra Club Coal Report). The increase in surface mining (eg. mountaintop removal) that provides fewer jobs than underground mining, accounts for much of this disparity.

In October 2010, the US Energy and Information Administration provided more data on jobs in the coal sector. It’s useful to take a look at the numbers to understand how misleading the “coal provides good jobs” myth is. The coal industry is a pro at giving people all over the country the impression that coal-mining jobs are unionized, or at least mostly unionized. Yet only 22% of coal mining jobs are union jobs and the number of jobs mining provides is falling as coal mines close. All told, there are 86,432 coal mining jobs. To put the number in perspective, there are more than eighty times as many people in prison, on parole, or probation in the United States as employed in coal mines. There are at least 40x as many truckers as miners, and well over 150x as many unemployed Americans as coal miners. Certainly these jobs are important, (especially to those whose paychecks comes from mining), but coal jobs do NOT support a core pillar of our economy. Coal mines employ only a tiny fraction, far below 1% of the US population, and these jobs are replaceable. (EIA) Per investment dollar, investments in wind and solar power would create at least 2.8x the number of jobs as coal; investments in conservation would create 3.8x as many jobs, and investments in mass transit would create 6x as many jobs as coal!

Peak Coal — Another economic factor

Investments in fossil fuels drive up fuel prices as economically recoverable fuels become scarcer, while investments in renewable energy make alternative fuels more affordable as technologies improve and energy markets grow. Already, most economically extractable US coal has been burned. U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) information on coal “reserves” does not take into account economic recoverability. Yet like every finite resource, at some point coal supplies will ‘peak’, meaning that as recoverable supplies dwindle the energy-return-on-investment (EROI) will be lower than can justify mining, processing, and transporting the coal. When this peak will occur is one of the factors that set the price of coal, and in turn determine the cost competitiveness of other energy technologies. The availability of coal is important to understand before making investments in coal technologies such as integrated gas combined cycle (IGCC), carbon capture and storage (CCS), and coal-to-liquids (CTL). Building a new wave of capital-intensive coal plants with the potential to generate electricity for 50+ years is a bad investment if coal peaks before the plant’s useful lifespan is lived out. Despite industry dubbing the United States the ‘Saudi Arabia of coal’ and describing a 200-year supply, a recent USGS study suggests that there may be only 20–30 years of economically recoverable coal left in the United States.

The report Coal: Resources and Future Production (2007) concludes that statistics on global coal supplies are flawed since they are based on poor data sets. For instance, several countries (eg. Vietnam) have not updated ‘proven reserves’ for 40 years. Other countries have dramatically reduced their coal supplies. Peak coal is just one of many reasons to transition from the highly polluting energy source.

While the costs add up they aren’t as easy to calculate as company profits. Luckily, the “Mining Coal, Mounting Costs: The Lifecycle Consequences of Coal” report produced by the Center for Health and the Global Environment (2011) keeps tabs on many of these externalized costs. Their best estimate for the “economically-quantifiable costs of coal” in 2008 totaled more than 345 billion.

Coal production and use destroys a sustainable future.

As mountains are leveled and water bodies contaminated, the coalfields become unlivable; a sustainable future is destroyed. Property values plummet when there is not potable drinking water or when the property is prone to flooding (from clearcutting). Tourism opportunities dry up, entrepreneurs go else, and people move away. Coal mining’s destruction is driving people away from their families and land in Appalachia. Appalachia can reduce poverty and diversify and restore its economy if mining is halted immediately. An end to mining would enable Appalachians to use the beautiful and bio-diverse mountains for locally-grown foods, a sustainable timber industry, and hand-crafted goods, among other life-sustaining economic ventures.

Coal Drives Climate Change and Ecological Destruction

In a desperate attempt to convince Americans that coal can be a clean, safe fuel source mined and burned long into the future, the coal industry spends millions every year denying climate change and perpetuating myths of “Clean Coal”. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Coal-fired power plants emit a third of the United States’ global warming pollution; coal mining releases methane (a potent greenhouse gas), carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide; and transporting it adds another 600,000 tons of nitrogen oxide to the environment.

Furthermore, mountaintop removal mining companies blowup and bulldoze our country’s most biodiverse mountains and forests. Instead of protecting this carbon sink, coal companies clearcut the forests and destroy historic sites (including family cemeteries). The EPA has estimated that MTR has already cleared more than a million acres of forests and mountains. In 2005 a Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement on MTR stated that mountaintop removal operations have buried and contaminated more than 1,200 miles of streams.

Films such as Low Coal capture the intense personal connections and histories many Appalachians share with the land in the coalfields. The stories offer testimony on why mountaintop removal must stop immediately.

All forms of coal – ‘clean’ (IGCC), carbon capture and storage, and liquefied – create environmental disasters.

“Clean coal” is a myth. It’s goal is to reduce air emissions, which is good and needed. However, that should not lull one into thinking that coal mining would be any less destructive. Indeed, mine sites employing coal washing treatments could make the slurry lagoons even more toxic as contaminants are removed from the coal. Such contaminants as radiation, mercury and fluoride don’t go away, they just go somewhere else.

See our pages on carbon capture and storage and so-called “clean coal” for more information.

Coal Calculus — By the Numbers

statistics are linked to sources/citations in above text

| 600+ | US coal plants |

| 600+ | US coal ash dump sites |

| 67 | Air toxins from coal |

| 13,200 | Coal deaths (2010) |

| 200,000 | Coal-triggered asthma attacks (2010) |

| 19,015 | Union mining jobs (22% of all mining jobs) |

| 20–30 | Years of recoverable coal |

| $345 Billion | Annual cost of coal |

| 0 | Coal plants built since 2008 |

| 100+ | Coal plants defeated by activists |